Recent

Looking for something specific?

Give our search bar a go!

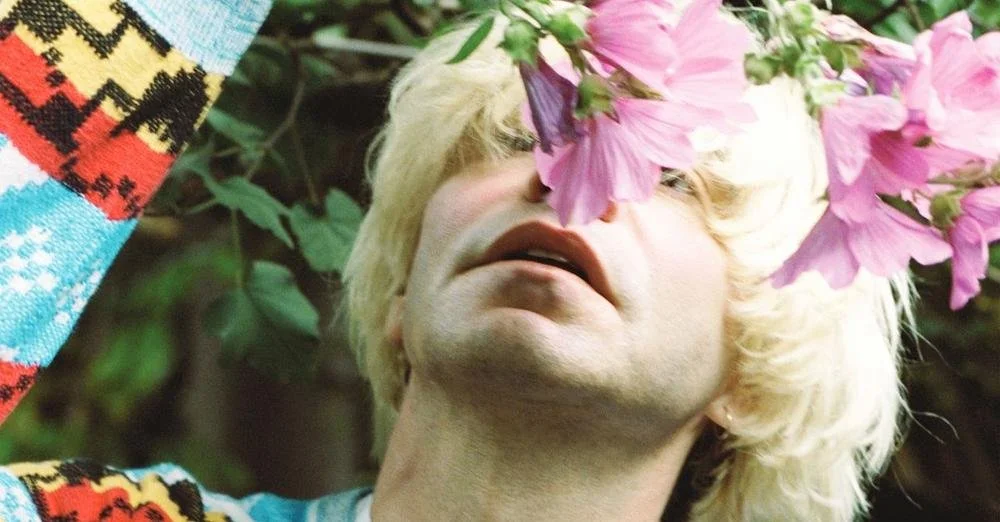

For Tim Burgess of The Charlatans, the best ideas come when he’s preoccupied. And ideally when he’s at the gym.

S.G. Goodman was raised a farmer's daughter and studied philosophy in college. This means that not only does she love to ponder, she has time do it during those long days in the field. The product of all the pondering? Amazing lyrics.

As an instrumental guitarist steeped in improvisation, Julian Lage isn't one for specific rituals. And that's why I loved this conversation: it's a deep dive into the abstract elements of creativity as we try to figure out where it all comes from.

Gavin Rossdale’s favorite lyrics are those with “speckles of blood, speckles of sweat.” The more truthful the writing, he says, the bigger the power.

Grian Chatten of Fontaines D.C. calls songwriting his “constant annoying companion. I have writing on speed dial 24/7.”

Madison Cunningham writes every day. No excuses. Because a writing regimen takes the pressure off those days when she’s just not feeling it.

Will Sheff believes in writing every day, first thing in the morning. But he’s also a firm believer in loafing.

from the archives

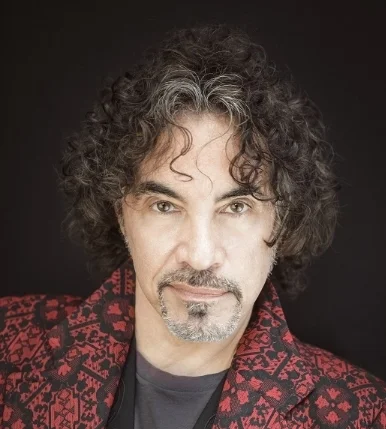

When I started this site in 2010, I had a goal: treat songwriters as writers, plain and simple. As someone with a Ph.D. in English Literature, I had read my share of interviews with poets, playwrights, novelists, and short story writers detailing their writing process. But what about songwriters? Aren't they writers too? Shouldn't they be included? So when John Oates started our interview by saying, "I've always looked at myself as a writer," I swooned. Because songwriters are writers. Period.

Indie

Will Sheff believes in writing every day, first thing in the morning. But he’s also a firm believer in loafing.

Falling asleep on the job is usually not a good thing. But Emily Haines says that if you’re in Metric, it can be a great thing.

A move to Upstate New York has given Derek Miller of Sleigh Bells two boons to his creative process: football and the chance to get really, really loud.

Lauren Mayberry of Chvrches has a songwriting process that involves spreadsheets, Pinterest boards, and hotel pens. And a jar full of scrap paper.

Steve Gunn’s songwriting process never stops. Even when he’s not writing, his receptors cast a long throw over his environment as he mines for ideas.

Whether he’s longboarding or reading to his kids or drawing, Bardo Martinez of Chicano Batman is always thinking about his next song.

“Raw source material is supposed to be crap,” Michelle Zauner says. “You have to allow yourself to be terrible.” Her best writing comes in the revision process, not in those “garbage” first drafts.

Josh Kolenik of Small Black draws from both Excel spreadsheets and Raymond Carver when he writes songs. He looks everywhere for inspiration. “It’s important to have a breadth of material to draw from,” he says.

There are days when the songs just won’t stop coming, says Bartees Strange. His job as an artist is to stand there and try to catch all those ideas. “It’s like holding a bucket outside in the rain,” he says.

The experiences of Tim Showalter (Strand of Oaks) and Jessica Dobson (Deep Sea Diver) during the pandemic couldn’t be more different. Showalter’s tour cycle for his last album Eraserland ended in February; this meant the quarantine had little impact on his songwriting cycle since he already planned on spending 2020 writing. Dobson fared differently: Deep Sea Diver released Impossible Weight in October, so of course they were unable to tour behind the album, which threw all their plans out the window.

For Stone Gossard of Pearl Jam and Mason Jennings, songwriting involves whole body movement and lots of swinging of the limbs. It also involves both temporal and emotional distance. And that distance was a big asset in creating Painted Shield, their self-titled album.

Sadie Dupuis has a studio set up in her house where she does most of her work for her band Speedy Ortiz and her solo project Sad13. Once she’s down there, she has no trouble getting into the flow of the creative process; in fact, she often has to tell herself to take a break so that she doesn’t work through the night.

The hard part is getting started down there in the first place. She often find her studio “overwhelming and stressful.” It puts too much pressure on her. And who wants to feel overwhelmed and stressed at the start of a project? Her solution is brilliant: she starts on her couch or her table, which she finds less intimidating because it doesn’t feel like work. Then, she says, “I'm excited to go down to the basement and continue. If I sit on my couch or sit at the living room table, it's so much less intimidating to get into a new project. I don't think I'm working, so it doesn't feel scary.”

The idea of ritual is an important one in the creative process. Some artists need the comfort of ritual to create, whether it’s a certain place, time of day, or even a favorite pen. Others thrive on the opposite: discomfort. It’s chaos that makes them thrive. And it’s this discomfort, this unpredictability, that has made Ariel Rechtshaid one of the most sought after and successful producers in the last decade because it’s what drives his creative instinct. He works the best when what he’s presented with—whether it’s an artist, instrument, or even chord structure—is unfamiliar to him.

“Woo hoo! I feel so energized!”

This was Tim Showalter’s first reaction when I told him we were wrapping up our interview, which had gone for over an hour. His next reaction? “Let’s do this again sometime!”

I could feel Showalter, the man behind Strand of Oaks, smiling during most of our phone conversation. He loves to talk about the creative process.

For his latest album Phoenix, David Bazan made a lot of phone calls. To himself.

Each day, rather than journaling, he’d use the voice memo on his phone for ten or fifteen minutes to talk to himself. These calls were a “meet and greet with myself.” And through them, he got to know himself better.

I was surprised when Courtney Barnett told me that she doesn’t like solitude when she writes. Almost all of the songwriters I’ve interviewed have told me that they need to be alone, for the simple reason that they can’t have any distractions. But when Barnett told me why she needs to be around the action, it made sense: how can you be a narrative storyteller if you write while facing a wall?

Marissa Nadler needs to write. It’s a therapeutic necessity: she uses it to process the events in her life. By her account, her best music happens when that need arises. But even if that need disappeared, Nadler would still be able to write because she’s so disciplined.

Don't be concerned for Eleanor Friedberger if you see her mouthing words or even mumbling to herself when she's out for a walk. It's her storytime. And it's during these times that song ideas come to her. "I tell very long and elaborate stories on those walks. True stories. As if I'm telling people a story of my relationship with so-and-so or the time that something happened to me."

Courtney Marie Andrews needs to be alone.

That is, she needs complete solitude when she writes. Where other songwriters thrive on a bit of commotion or even chaos around them, not Andrews. She needs solitude because it provides her the best chance for self-reflection and an "uncluttered headspace" in the songwriting process. And she has to know that she's alone too. But she doesn't necessarily need to be at home when she writes: in fact, she often prefers someplace new. "I think it's more that I like to travel and feel out of my element, and I think my best songs come from that space. I lean towards writing songs in unfamiliar places," Andrews told me. Her process also involves what she calls "chunk writing." She doesn't like to write on tour; that's where she collects all of her notes for the later songwriting process. But when she gets off tour, she blocks off a two-week chunk on her calendar and does nothing but write.

Matt Lowell of Lo Moon grew up playing hockey. "I was obsessed with it," he told me. Lowell was at the rink every day, but part of this obsession can be traced to how much he watched the sport. It was a natural extension: the first thing Lowell wanted to do after watching hockey on television was play it.

The same can be said for Lowell's love of reading. When he reads a lot, he writes a lot. And when he's not reading, writing is difficult. It's an easy connection. For the songwriters or writers reading this interview, you won't be a good writer unless you read. It's impossible. Just read the interviews on this site. The songwriters are voracious readers, and Lowell knows this. He knows that his talent as a songwriter depends on his exposure to other people's words. "I’m not really inspired by everyday life," Lowell told me. "I’m not that inspired by the things around me. But when I’m reading something, or if I see an amazing film, or if I’m jamming with my band mates, that’s when the sparks come." By his own admission, the band's schedule has kept him away from his books, and that bothers him. "I'm upset that I haven't been able to read that much," he said.

Jessica Lea Mayfield owns a blue tote bag. This in itself is not unusual: you probably have a tote bag too. But it’s not a stretch to say that Mayfield’s blue tote bag is her life. It contains almost everything she’s ever written, all the way back to when she was a child. There are scraps of notebook paper, receipts, utility bills, pieces of cardboard. And she’s written on them in pens, pencils, eyeliner, and crayons, among other things. Whenever Mayfield has a thought, she writes it down and puts it in the bag. And when it comes time to write a song, she will often dump the bag’s content all over the floor and search for an idea or a verse or phrase that fits the melody for the song she’s writing.

Every writer has a ritual, some consistent part of the writing process that brings them the comfort or confidence to be productive. Ted Leo has one: stacks. Stacks of things. When Leo is around the house, he carries with him from room to room a stack of pads, some pens, his phone, and his Roget's Thesaurus. And when he sets them down, they are each their own stack, not one giant stack. Almost like a fortress of words around him.

Leo's lyrics have been rightfully praised for years, and I have to think that much of this has to do with his voracious reading habit. It's not possible to be a writer unless you read. It's just not. Leo is a good example of that; he goes down rabbit holes of genres or authors or topics, especially while on tour. And these are some pretty dense topics. That's why, after one tour, Leo was able to riff about 70s urban planning in the UK and Russian constructivist architecture with ease. And while he may not have written any songs about these topics, he says that on some level all of that reading made him a better, and a more thoughtful, songwriter.

You know Dan Wilson. You may not think you know Dan Wilson, but you know Dan Wilson. How do I know that you know Dan Wilson? Because it's closing time somewhere in the world as I'm typing this and as you're reading this, and there is no way in hell that you haven't heard that song. Which, by the way, I still love.

You also know Dan Wilson because you know Adele and the Dixie Chicks. He co-wrote Adele's "Someone Like You" and the Dixie Chicks' "Not Ready to Make Nice." He won two Grammys in 2007: Song of the Year as co-writer on "Not Ready to Make Nice" and Album of the Year for the Dixie Chicks' album Taking the Long Way. He again won an Album of the Year Grammy in 2012 for Adele's album 21. The list of artists he's either written with or produced is dizzying: Taylor Swift, Nas, Pink, Weezer, John Legend, Josh Groban, Chris Stapleton, Spoon, Preservation Hall Jazz Band, My Morning Jacket, to name a very small few. He's got indie street cred too: he worked extensively on Phantogram's 2016 album Three, including a co-writing credit on every song except one.

If you ever email Broken Social Scene's Brendan Canning, a word of advice: don't ever greet him with "nice to e-meet you!" This is horrible, and Canning hates it. He's also not a fan of any reference to "hump day" in emails he gets on Wednesday. I agree with Canning's point, and I hate these phrases because they are lazy. Canning probably does too, but as a songwriter who creates original art, hackneyed phrases like these must especially make him cringe.

Of course, I might be reading too much into this. But Canning is always creating: he cooks, he gardens, he plays soccer, and he DJ's. "I live life with my curiosity piqued," he told me. In fact, you can often find him on the streets of Toronto on his bike, staring at people and wondering what their stories are. The important thing is that Canning is always keeping his brain going in some fashion. So if you're in downtown Toronto and notice Canning staring you down, there might be a Broken Social Scene song in there somewhere.

Back in June 2016, Alaina Moore of Tennis (whom I interviewed for this site) emailed me about a new band she discovered. She wrote, "I just found a band called Big Thief with a debut album, Masterpiece. It's unbelievably good, and the song "Real Love" has a guitar solo that literally made me cry."

That guitar solo is played by Adrianne Lenker, Big Thief's vocalist, guitarist, and songwriter. Since Masterpiece's release last year, the band put out Capacity, and on the strength of those two incredible albums (both on Saddle Creek Records), the band has leaped to the top of many critics' short list of best new bands, or just best bands period. And for good reason: the music is powerful and Lenker's lyrics are intensely personal. Much of this has to do, I think, with how Lenker travels through this world. She treats everything she sees and everything she hears as a work of art. The world is her palette. "My mind puts frames on everything," she told me.

Yukimi Nagano of Little Dragon is a book hoarder at her local library in Sweden. She browses the stacks across all subjects, from photography to poetry to flowers. Then she walks out with as many books as she can carry. When she gets home, she peruses those books for both words and images. Sometimes the words make their way into her songs, and other times the images give her ideas to spin off of. "It could be a book about flowers, for example, and I might find a beautiful name for a flower that could be a song title," Nagano told me. And when she gets home, she does most of her writing in the kitchen. There's something about the "nice, soothing hum" of her refrigerator that's conducive to her creativity.

For today's interview, I have a companion. Last November I interviewed Theresa Wayman from Warpaint. It remains one of my favorite interviews. I recently read that Wayman was a big fan of Little Dragon, so I asked her if she wanted to interview Nagano with me. She gave me an enthusiastic yes, and somehow we made this happen: I was in New York, Wayman was in Rhode Island, and Nagano was in Sweden. We had a fantastic discussion about the creative process.

John Darnielle of the Mountain Goats was nervous when he saw the word "process" in the title of this site. Process implies routine, and Darnielle doesn't really have a routine when it comes to songwriting. In fact, he eschews the idea. If he writes every day, it's a descriptor of his routine rather than a mandate. Keep a journal? Heck no, because Darnielle feels pretentious writing about himself. He wants to demystify the songwriting process; he doesn't want to see it as something that only happens when certain factors align.

By my count, Sylvan Esso's Amelia Meath is in the middle of reading seven books now. She's reading poetry, fiction, non-fiction, plays, a biography, and I'm sure some others she didn't mention in our interview. I was not surprised when she told me this. Follow Meath and her bandmate Nick Sandborn on any form of social media, and you'll see creativity everywhere. Meath is of course known for her work now in Sylvan Esso, but there's much more. She loves acting and even went to college to study it. (This is not a surprise if you've seen her lithe and theatrical stage moves). She loves to make collages. And she wants to start writing a tv pilot. Oh, and she once did a ton of freewriting about LeBron James.

Meath's songwriting process involves some routines, even though she does most of her writing "in the air." She eschews computers and prefers pen and paper for her lyrics. But not just any pen and not just any paper: for now it's a Poppin pen and college ruled composition notebooks. Part of her lyrical process involves writing the same verse over and over; in fact, some of her notebooks are filled with just one song.

Any artist will tell you that discipline is a necessary component of their creative process. Anyone who sits around waiting for the muse is probably not long for the craft. You have to work at it. Theresa Wayman of Warpaint certainly adheres to this idea: she creates something every day, even if it's nothing great. She told me, "Even if you're a creative person, it's important to go to work every day. . . . I have to exercise some aspect of myself, even if I create something that I never want to hear or see again. At least I've accomplished something if I do that. . . . You have get through the crap to create something beautiful."

Wayman wasn't always this disciplined, though. Another component of the creative process is the willingness to change your routine to stay energized creatively. To Wayman, that change meant becoming more disciplined. Using discipline as a way to disrupt the creative process would appear to be a paradox, although it really isn't.

Regardless of what kind of art you create, some level of self-awareness is important. If you're a songwriter, you may marvel at the miracle of inspiration and how sometimes songs just fall into your lap. But at some point, you have to think about your process: you have to think about the parts that work, the parts that don't work, and why they do and don't. Successful songwriters have that level of self-awareness. It's hard to be productive if you're oblivious to your process. Jenn Wasner knows what works and what doesn't work, and this is one of the reasons why she is so prolific and so talented

Songwriters on reading

“I don’t think you can be an adept lyricist without having knowledge of other people’s work. If we’re talking poetry, I still love Baudelaire. I still love the Beat poets, people like Gregory Corso. My favorite Beat poet is a little more obscure, Bob Kaufman.

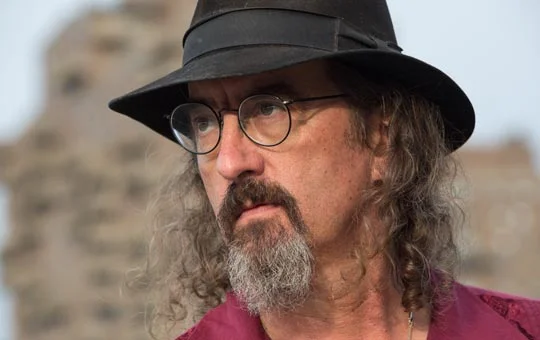

But I read everything. I'll read fantasy stuff like Gene Wolfe then I’ll read Knut Hamsun's Growth of the Soil, then Jean Giono then Gustave Flaubert. I don’t restrict myself to anything. I’m all over the place: H.P Lovecraft and Arthur Machen. I would have equal time to read Israel Regardi’s The Golden Dawn as I would read Francis Pryor’s Britain B.C.”

- Chris Robinson, The Chris Robinson Brotherhood and The Black Crowes

Follow us on Social

Americana

Allison Russell and Aoife O’Donovan are celebrated songwriters—and working moms. This makes for a songwriting process in which the only ritual is recognizing that you don’t have one.

A good songwriting process for Emily Scott Robinson involves bank pens and vacuum cleaners.

Andrew Marlin of Watchhouse (FKA Mandolin Orange) gets his best writing done between midnight and 4am.

BJ Barham of American Aquarium and poet/novelist Joe Wilkins discuss the powers of poetic observation and why reader empathy is important. And listen to BJ explain why he’ll never write a song about pancakes.

I first interviewed BJ Barham of American Aquarium in November 2020, and we had so much fun we decided to do it again! This time we added a third: S.A. Cosby, author of one of our favorite books from 2020, BLACKTOP WASTELAND. Watch these two creative heavyweights discuss the writing process and books and music.

For both Sarah Jarosz and Margaret Glaspy, the creative process doesn’t allow for much off time. Jarosz doesn’t write on tour: it’s where she collects her ideas. And when she gets home, that’s when she sifts through all those ideas. “Even if I’m not working on a song, I’m always checking into the creative process every day,” Jarosz told me. Glaspy’s process involves using improvisation as a part of her songwriting process, “acting like I know how the song is supposed to go,” she says.

Like many artists, Katie Pruitt and Molly Tuttle have found the creative process to be a hard road over the past year. But as you’ll hear, when those songs do come, dreams are an especially fruitful time: both women have been awoken in the middle of the night by incredible melodies running through their head.

Jeremiah Fraites of The Lumineers wrote most of his new solo album Piano Piano pre-pandemic, but, like most songwriters, he says that the past year has wreaked havoc on the creative process. “Last year was not a good headspace to write from. All that isolation was not good. There was, and is, an underlying element of fearfulness that’s bad for the creative spirit,” he. says.

Most artists need external stimulation, some interaction with their environment, to create. That’s why the pandemic has made it difficult for songwriters: while some have taken advantage of the lull in touring to write, many others have found the isolation debilitating to their creative process. The two Nashville-based songwriters I interviewed in this video, Langhorne Slim and Jillette Johnson, have struggled at times to write songs during quarantine.

B.J. Barham of American Aquarium has a writing process like no songwriter I’ve ever interviewed. Plenty have told me that for them it’s as simple as scribbling lyrics on a sheet of paper. But not Barham. His songwriting process is akin to the research routine of a graduate student.

There are two points during my interview with Patterson Hood of Drive-By Truckers and Lilly Hiatt when each reaches to the sky, grabs a piece of air, and pulls it down. Both were describing their songwriting process: songs come from the muse, from the sky, from somewhere they can’t explain. And it’s their duty to grab that song, pull it down, and create it.

Elizabeth Cook and Lydia Loveless have some great advice for writers of any stripe in this interview. Like Cook, I’ve always told people that good writers understand that the actual pen-to-paper part of the writing process is only a small part of it. And like Loveless, I don’t think an idea for writing has ever come after sitting down to think about what to write.

We talk about how Pilot Pens (black), hot toddies, and voodoo deities played an important role in the creative process behind their last albums. Watch our Zoom interview to find out which one of them ate corndogs on Christmas day as part of that process!

Dave Hause and Kathleen Edwards have known each other for a while and are huge fans of each other’s music, so this was a fun conversation on the creative process. We talked a lot about whether large expanses of time make them more productive, how reading affects their songwriting process, and what they do when they get stuck. And how twins and dogs affect their songwriting process.

Jim James of My Morning Jacket wants to be a happy songwriter. And a healthy one too.

A fair amount of the songwriters I’ve interviewed extol the virtues of writing while hungover. Others talk about how marijuana helps their creativity. Still others credit sobriety with making them better thinkers. But few, like James, have openly advocated physical exercise as a means to boost creativity. He wants more songwriters to get out of the studio and into fresh air. He’s also sick of the idea that misery is an essential component to writing.

Marissa Nadler needs to write. It’s a therapeutic necessity: she uses it to process the events in her life. By her account, her best music happens when that need arises. But even if that need disappeared, Nadler would still be able to write because she’s so disciplined.

Courtney Marie Andrews needs to be alone.

That is, she needs complete solitude when she writes. Where other songwriters thrive on a bit of commotion or even chaos around them, not Andrews. She needs solitude because it provides her the best chance for self-reflection and an "uncluttered headspace" in the songwriting process. And she has to know that she's alone too. But she doesn't necessarily need to be at home when she writes: in fact, she often prefers someplace new. "I think it's more that I like to travel and feel out of my element, and I think my best songs come from that space. I lean towards writing songs in unfamiliar places," Andrews told me. Her process also involves what she calls "chunk writing." She doesn't like to write on tour; that's where she collects all of her notes for the later songwriting process. But when she gets off tour, she blocks off a two-week chunk on her calendar and does nothing but write.

By her own admission, Whitney Rose is an "unapologetic romantic." This isn't surprising if you know her music: it's about as authentic and throwback as you can get in the country music world. There's a little bit of Patsy Cline, some Loretta Lynn, and even some Dolly Parton too.

But Rose is old school in other ways too. As you'll hear in almost any song she sings, she's a storyteller. Rose laments the art of storytelling in song as a dying art (something Evan Felker of Turnpike Troubadours told me in our recent interview). And don't even get her started on the state of penmanship instruction in schools. She told me that she was "appalled" to learn her two younger siblings aren't even being taught cursive in schools. Just typing. Unsurprisingly, Rose has never used a computer to write her lyrics. And she can only write under one condition: there can be no one around, not even anyone in the house, when she writes. Rose's writing happens spontaneously. She's been known to walk out of restaurants and parties, no matter who she's with, when she feels a song coming on. She goes home and goes into, in her words, "musical labor."

Evan Felker, songwriter and guitarist for Turnpike Troubadours, has his own version of the nuclear football, the bag that never leaves his side when he's on the road. It contains everything he needs to write a song: his laptop, a composition notebook, and a legal pad. Each serves a specific purpose. The legal pad is for song ideas and random lines, and for this he uses a pen. The composition notebook is for the lyrics, and for this he uses a pencil. Then the computer is where the fully formed song takes shape so that he can copy and paste to see where the lines work best.

As you may have read in the last few days, Turnpike Troubadours have a new album out October 20 called A Long Way From Your Heart. Felker details some of his songwriting process behind the new material in our interview. He decided to write songs with a narrative bent filled with fictional characters inspired by the people he's known throughout his life. Many are from the area around southeastern Oklahoma where he grew up, from places like the factories and mills he worked after finishing tech school. Felker co-wrote one of the new songs on the album, "Come As You Are," with his good friend Rhett Miller of the Old 97s. (I interviewed Miller a couple of years ago, and I have to thank him for putting me in touch with Felker.) Here's what Miller recently told me about Felker...

"Adjectives and adverbs are not what we need to be singin'," Tift Merritt told me during our interview. Like any good songwriter, the Grammy-nominated artist favors economy of words and simple language in her lyrics, just as two of her biggest literary influences are Cormac McCarthy and Raymond Carver. "A lyric needs to feel as if somebody could've spoken those words while standing in line at the post office," she said.

Merritt studied creative writing in college and has been writing across genres for a while. Songwriting is just one of her many creative outputs. But while Merritt might favor economy of language in song, her description of her writing process is filled with metaphors. She talks of "rolling around" in her creativity during the early stages of the process and of discarded song ideas as "pebbles on the trail to the next idea." She typically spends her mornings on words and her afternoons on music, because the lyrics require the sharpness of the morning. After lunch, Merritt says, that's when "you invite an instrument to come sit down with you."

M.C. Taylor will tell you that he's not a narrative songwriter. There may be a story behind the songs, but they don't really tell a story. And even if they did, he wouldn't tell you what those songs are about because that's not his duty as a writer. Taylor would never dare tell you what meaning you're supposed to glean from his lyrics. "Part of my mission with Hiss has been to make emotionally complex music, where you play it for someone and they can't quite tell whether it's happy or sad. That's the core of my music: using it as a mirror for what my life feels like, because my life is both happy and sad, usually at the same time. My songs are about whatever you want them to be about. You have your idea and I have mine, and I would never disabuse anyone of their notion." he told me.

You don't win four Grammy Awards and receive eleven additional Grammy nominations by letting the muse come to you. You don't have eleven #1 country singles and twenty-one Top 40 country singles by waiting for inspiration to strike. And you certainly don't become a member of the Nashville Songwriter's Hall of Fame by writing only when you feel like it. When you're Rosanne Cash, you write. And when you're not writing, you're thinking about writing.

Jim Lauderdale has been called a "songwriter's songwriter," and for good reason: he's written songs for artists like George Strait, The Dixie Chicks, Elvis Costello, Blake Shelton, Patty Loveless, Vince Gill, and Gary Allan. He's released 28 studio albums since 1986, with a new one out this spring called London Southern. He's won two Grammy Awards. He's also the host of the fantastic "Buddy and Jim" show on Sirius/XM Radio. In short, Lauderdale is enormously respected in the country, bluegrass, and Americana music genres.

Everyone offering career advice seems to want to steer people away from the humanities. Don't be an English major, they say. You won't make any money. Singer/songwriter Allison Moorer has fortunately dispensed with this silly bit of advice: she's finishing her first semester at The New School in Chelsea, where she's getting her MFA in creative non-fiction. As someone with a Ph.D. in English Language and Literature, I fully support her new career path.

I know no better demonstration of the link between reading and songwriting than the advice Ray Wylie Hubbard gives songwriters: "Don't just listen to 'The Ghost of Tom Joad.' Read The Grapes of Wrath. That’s a classic song, but Springsteen wouldn't have written it if he hadn’t read Steinbeck." Of course, Steinbeck is probably a beach read for Hubbard. His staples are writers like Baudelaire, Verlaine, and Rimbaud. And before he goes to bed each night, he'll often pull down Dante's Divine Comedy from the bookshelf to see how that text might inspire his songwriting.

James McMurtry wants his old iPhone back. The singer-songwriter hasn't been the same writer without it. And it's all because Apple changed its Notes app.

In the days before computers were the default method for composition, McMurtry wrote lyrics on legal pads. He has boxes filled with legal pads filled with lyrics. He became intensely familiar and comfortable with those yellow pages; there was something about that yellow and those lines that made the words pour forth from his felt-tip pen. McMurtry eventually turned to computers, but with them he sacrificed portability. Cell phones solved that problem. And when McMurtry found that the Notes app on his iPhone 3 looked like that old yellow legal pad paper, well, the words flowed. It was creative nirvana.

It is a testament to Kevn Kinney's stature among songwriters that other artists like Matt Nathanson and David Bazan tweeted their enthusiasm when I announced that Kinney would be featured here. Kinney has fronted Drivin' N Cryin' for close to 30 years now, and I've been a fan for most of those years. Kinney is a native of Milwaukee but the band started in Atlanta, so naturally they've been pegged as a Southern rock band, whatever THAT designation is. I prefer to see them as a rock band, plain and simple, with early staples like "Fly Me Courageous," "Honeysuckle Blue," and "Can't Promise You the World." The band is still active in both recording and touring, releasing one LP and four EPs since 2009.

Jay Gonzalez: Drive-By Trucker, Bay City Roller. Sure, Gonzalez is guitarist and keyboard player for the Truckers. But his solo stuff sounds nothing like his Truckers work. Gonzalez is an unabashed fan of 70s power pop, bands like The Sweet and The Bay City Rollers. In his own words, "I possess the attention span of a goldfish. I’m a sucker for short pop songs filled with hooks and devoid of filler." The defining element of 70s power pop is the melody. It reigns supreme. Lyrics exist merely to enhance the melody, not to tell a story. According to Gonzalez, "I think the ideal situation is to have a song that if it were an instrumental or if it were a Muzak song, you would recognize the melody. It’s strong enough to stand on its own without the lyrics."

In the nearly 150 interviews I've done for this site, one thing stands out: songwriters are voracious readers, much more so that the general public. They read all the time. They read novels, they read short stories, they read non-fiction. But curiously, not nearly as many read poetry as I would expect. That surprises me, given the similarities between song lyrics and poetry.

Amanda Shires is the exception. She reads poetry with a passion. But she's taken it one step further: Shires is pursuing her MFA in poetry from Sewanee, and she's almost finished. It's no surprise that her coursework has had a tremendous impact on her songwriting, since she's learning about the craft of poetry But it hasn't been without its challenges. While it's easy for Shires to share her songs with an audience, sharing her poetry is a different experience.

Ray Benson is best known as the co-founder of the country music band Asleep at the Wheel. The band, founded in 1969, has won nine Grammy Awards. Asleep at the Wheel is a contemporary torchbearer for the subgenre of country music known as Western swing, a more danceable kind of country music that originated in the 1920s.

But the 63 year-old Benson has a solo release out now calledA Little Piece, only his second solo album. It represents a departure from his Asleep at the Wheel material; it's more personal and was written from a much darker place, according to Benson. I saw Benson play an in-store at Waterloo Records in Austin a couple of months ago, where he showcased his new material backed by the excellent band Milkdrive. I had never seen Benson before, and his performance was fantastic. He's a great storyteller and performer whose baritone serves as the ideal complement to his new material.

For Tim Burgess of The Charlatans, the best ideas come when he’s preoccupied. And ideally when he’s at the gym.