Kathleen Edwards and Dave Hause

“I keep pushing the goalposts back on a new album because we have to wait and see what we're in for. What will our lives be like in a couple of months?”—Dave Hause

“When I sit down to write, the house has to be clean. Also, the dogs have to be walked because they need to f**k off and leave me alone.”—Kathleen Edwards.

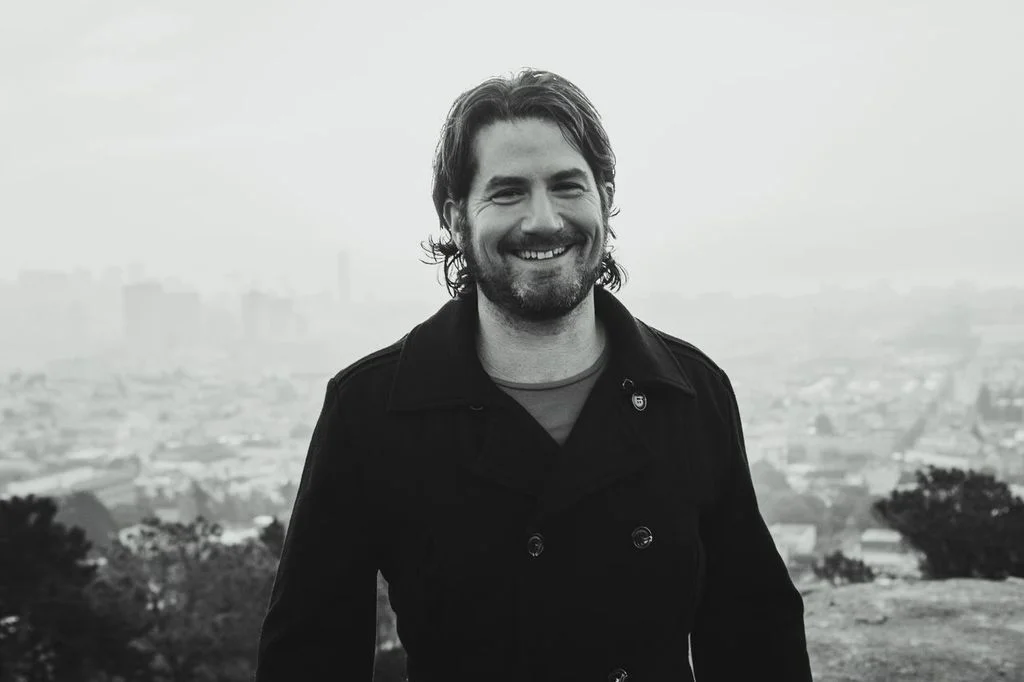

Dave Hause and Kathleen Edwards have known each other for a while and are huge fans of each other’s music, so this was a fun conversation on the creative process. We talked a lot about whether large expanses of time make them more productive, how reading affects their songwriting process, and what they do when they get stuck. And how twins and dogs affect their songwriting process.

Watch our Zoom interview below or listen to the podcast!

Artists are always searching for the ideal creative state, that perfect time when the songs effortlessly flow. For both Anaïs Mitchell and Charlotte Cornfield, that ideal state involves, well, not really being aware of when they’re in that ideal state.

It is a testament to Kevn Kinney's stature among songwriters that other artists like Matt Nathanson and David Bazan tweeted their enthusiasm when I announced that Kinney would be featured here. Kinney has fronted Drivin' N Cryin' for close to 30 years now, and I've been a fan for most of those years. Kinney is a native of Milwaukee but the band started in Atlanta, so naturally they've been pegged as a Southern rock band, whatever THAT designation is. I prefer to see them as a rock band, plain and simple, with early staples like "Fly Me Courageous," "Honeysuckle Blue," and "Can't Promise You the World." The band is still active in both recording and touring, releasing one LP and four EPs since 2009.

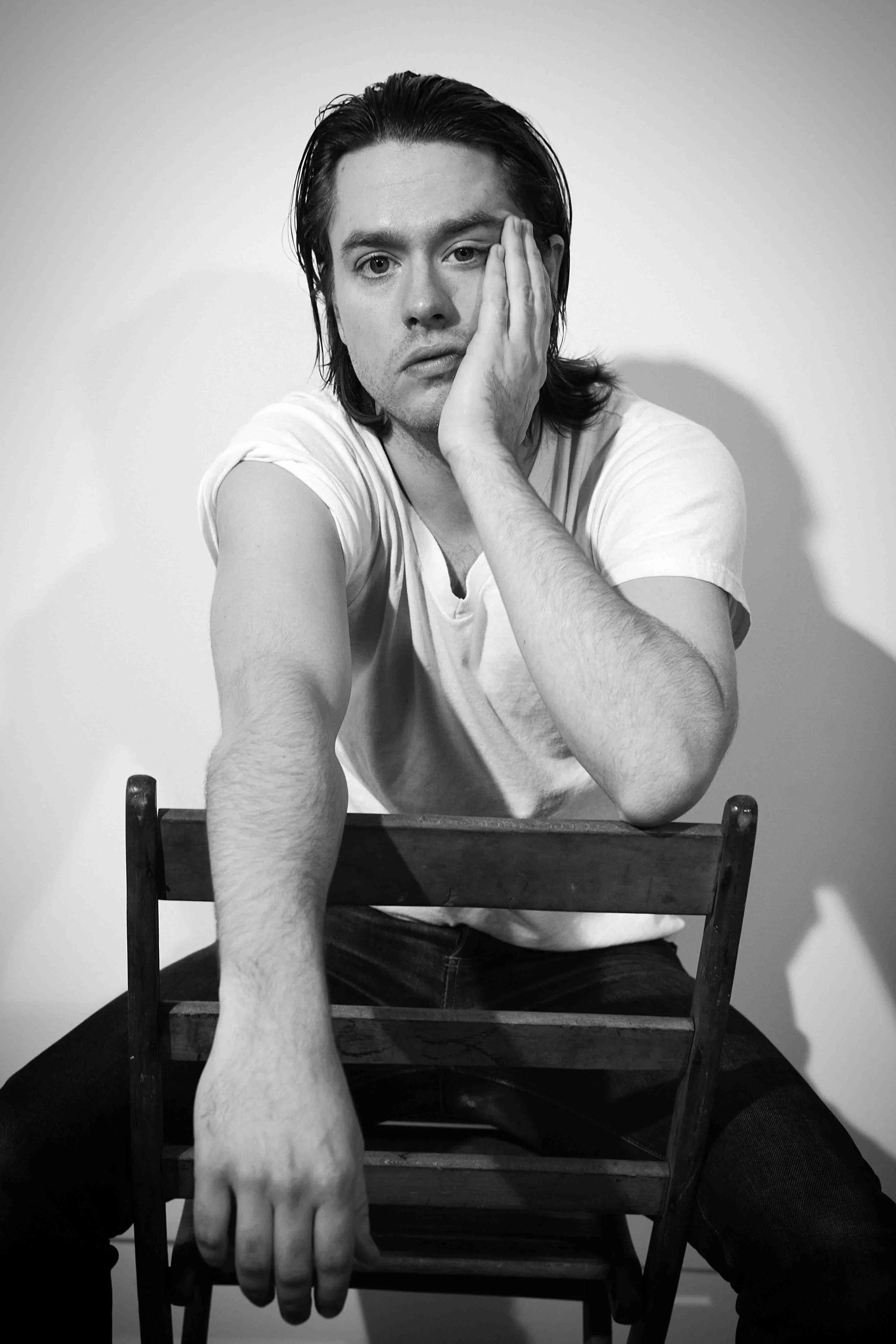

You may not know that Matt Nathanson has a writing partner. The problem, though, is that Nathanson doesn't want this guy around. In fact, Nathanson told me, he'd love to "tape his mouth shut and stuff him in a trunk." And even worse: this guy is an assassin.

This assassin is in Nathanson's mind. It's the part of him that tells him not to write certain words or ideas. The assassin is there to kill Nathanson's words by telling him that what he's writing is "dumb." And Nathanson hates the assassin, because when he's around, creativity suffers. Nathanson does his best to keep the assassin at bay so that he can write from the most honest and unselfconscious perspective he knows.

Read my interview with Matt Nathanson about his songwriting process. We talk about the assassin, morning puking, and shitting songs. It's long, sure, but worth every word. Of the 160 interviews I've done, this ranks as one of my favorites because Nathanson is so introspective. He doesn't just tell me about his process, he reflects on it and talks about what it says about him as a person.

By his own admission, Johnathan Rice has a "mysterious" writing process. He doesn't think he's ever written the same way twice. Yet his best songs have always come fully formed; that is, they don't even appear until he sits down to play, when they pour out of him all at once. Of course, this doesn't happen very often: he's been working on a song about the race horse Barbaro for a few years now, and despite all of his tinkering, Rice still hasn't released it because he's not happy with it yet.

Rice is a "voracious" reader, and I love his answer below about how all that reading has made him a better songwriter. Rice has also learned a great deal about himself through his many collaborations, including with Elvis Costello and of course Jenny Lewis with Jenny and Johnny.

Before talking to Ryan Bingham, I watched some of his videos on his YouTube channel. Several of the commenters pointed out that his singing voice sounds nothing like his speaking voice. And it's true. I couldn't help but think about this when he talked about songwriting as a form of therapy for him, a way for him to get things off his chest. When he pointed out that the lyrics sometimes emerge from his subconscious, that singing/speaking voice dichotomy made sense: perhaps that singing voice is different because it represents something deep inside, a window unto his emotional state.

Bingham calls writing "a very personal act" for him. He's protective of the space he creates to write, both emotionally and physically. His best lyrics come out all at once, because a song that takes too long loses the original, raw emotion. And his writing is cyclical: he soaks in his environment on the road and almost never writes there. Once he's home, he writes about those experiences in a short, powerful burst, "venting and getting those feelings off [his] chest." Once those songs and feelings are out, he stops, and he feels not one once of guilt for not writing for the next few months while he gathers those experiences on the road again.

Allison Russell and Aoife O’Donovan are celebrated songwriters—and working moms. This makes for a songwriting process in which the only ritual is recognizing that you don’t have one.